Meshkati has collaborated with arts writer Richard Unwin to explore the prominent role hair has played in art history, revealing some of the reasons behind its extraordinary visual power.

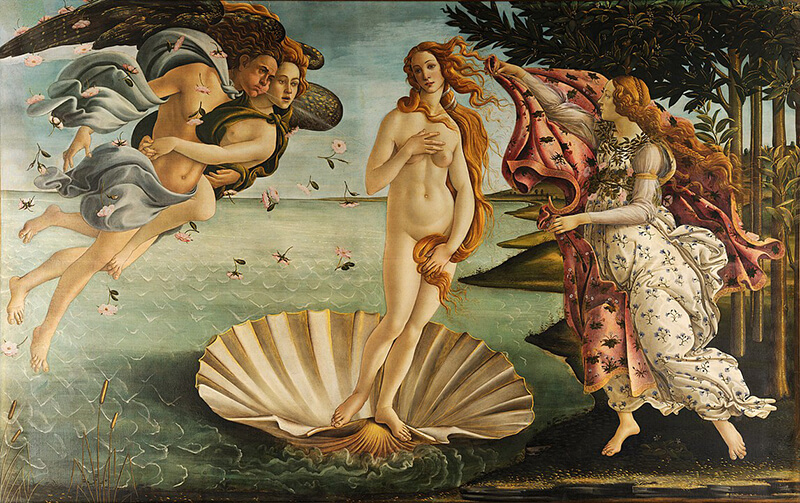

Throughout history, hair has been a distinctive and uniquely perceived part of the human body, seen as a defining feature of identity and status and used as a means to express a sense of self or belonging to the world. The cultural importance placed on hair has been conveyed through artwork and artefacts produced around the world, from tribal masks and sacred objects to the golden, wind blown strands in Botticelli’s famous composition ‘The Birth of Venus’. In that Renaissance masterpiece the goddess Venus stands resplendent on a fan-shaped seashell as personifications of the wind guide her towards the shore. Longer than might be possible were she human, the goddess’ hair acts a subtle drape, partially protecting her modesty. More than anything, though, Botticelli uses the hair to present Venus as divinely vital, a herald of the arrival of beauty and love in the world.

The ideals to which artistic depictions of hair have aspired have often been drawn from iconic figures in the classical past. Descriptions of Alexander the Great as having a lion’s mane of blonde hair provided one such guide for the appropriate way to generously portray male subjects. The link between hair and power has similarly been perpetuated in the way mythical figures such as Heracles (the Roman Hercules) and Achilles have repeatedly been depicted with abundant hair. The story of Heracles is itself sometimes seen as analogous to that of Samson, the Biblical character whose superhuman strength is famously inseparable from his hair, based on the Jewish Nazarite vow, which includes the commitment to God to refrain from taking a razor to the scalp. After teasing his duplicitous lover Delilah with false means to sap his strength, Samson fatalistically reveals his secret to her, leading to his capture and blinding by his Philistine enemies. Ultimately, though. Samson’s hair – cut by a servant at Delilah’s command – grows back and his power returns, enabling him, like Heracles, to choose the manner of his own death and ensnaring his captors in the process.

Botticelli’s Venus is just one example of the central role hair has played in western art history. While the skin of Renaissance subjects was frequently rendered in smooth, alabaster tones, for instance, it is often the hair, and headdresses, that help differentiate one person from the next. Similarly, the intricate, textural depiction of hair in both classical and Renaissance sculpture is one of the medium’s most notable features, helping convey a lifelike quality to individual figures and confirming the mastery of the maker. Given their preference for idealised visions of female beauty, a subsequent affection for hair is seen in the work of the 19th century Pre-Raphaelites, with the sensuous, free-flowing locks painted by artists such as John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti continuing to influence stylists and fashion photographers today.

Half a century after the Pre-Raphaelites made hair the focal point of paintings such as a Rossetti’s ‘Lady Lilith’, Alphonse Mucha reproduced similar themes and imagery in a more stylised, Art Nouveaux form. In Mucha’s fairytale world, the long, exceptionally healthy hair of his female subjects is used to entwine them with nature, evoking an organic purity that lifts the bearer onto a magical or spiritual plane. Influenced by forebears like Mucha, in the more radical, Secessionist paintings of Gustav Klimt hair again plays its part in a magical tableaux, but here the exuberant, pillows of hair seem to wrap and protect the subjects, often while they sleep, cocooning them in a world of dreams and the inner-self. Writing in the 1850s, Charles Baudelaire explored the corresponding power of a person’s hair to transfix a lover in his poem La Chevelure, finding himself carried by the scent and caress of one particular head of curls to exotic lands and the depths of an all-encompassing ocean. The perception of hair as an intimate extension of the self, to be nurtured and cared for, is something picked up on in Edgar Degas’ extensive series of bathing-related artworks depicting women washing and combing their hair: a theme also common in Japanese art. Such portrayals of personal connections with hair elucidate one reason it has played such a prominent cultural and societal role, bound as it is to the way we understand ourselves and inhabit our own bodies.

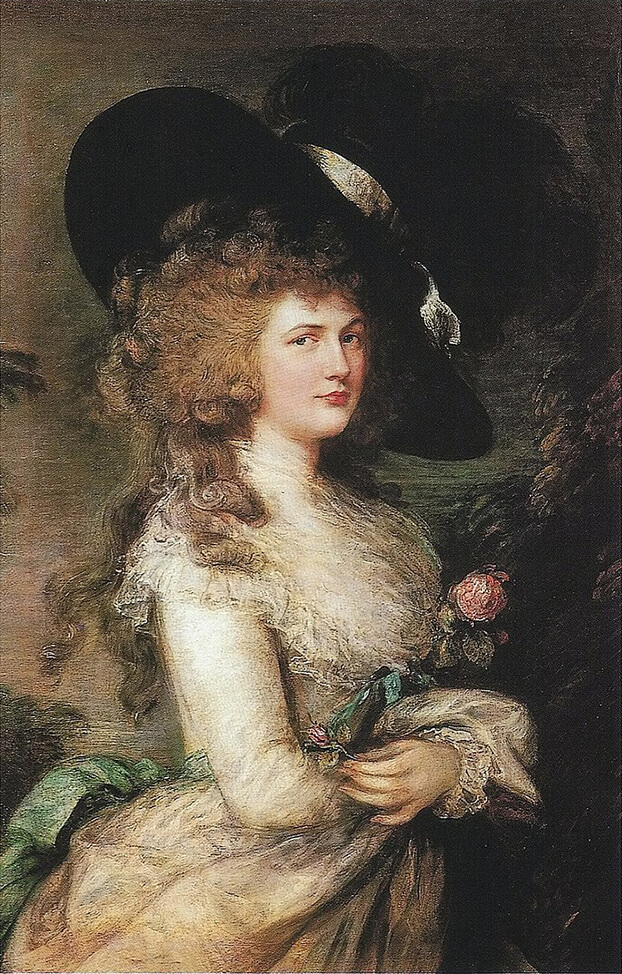

While we might think of the elaborate styling of hair as a relatively modern fascination, the artistic record points instead to an enduring human concern. In one notable 18th century portrait of Lady Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, by the English painter Thomas Gainsborough, for example, a confident young woman looks out to meet the viewer’s gaze. Dressed in a white gown and holding a pink rose, the painting portrays a society beauty who embodied the cultural zeitgeist of her age. At the centre of the painting is the Duchess’ hair, auburn and exuberant as it tumbles over her shoulders and back, topped by an oversized, angled hat. A friend of Marie Antoinette and ancestor of Princess Diana, Georgiana was a noted political trailblazer over a century before the achievement of female suffrage in Great Britain, as well as being a fashion icon and social celebrity. Known for her radical sense of style, her elaborate hair styles and headdresses drew on French fashions in an age when the styling of female hair had perhaps reached its apogee. Aristocrats and royalty would sit for hours as hairdressers and their assistants created theatrical, towering canopies of hair. The hairdressers themselves would sometimes also become public names, most notably in the form of Léonard Autié, Marie Antionette’s ‘Coiffeur de la Reine’ and the inventor of the era-defining, voluptuous pouf style. In Georgiana’s case, though, it seems the quality of her hair enabled her to impress with both outlandishly dramatic styles and the more organic, informal look captured by Gainsborough.

Hair has seemingly always had this special power, associated as it is with traditional notions of beauty and fertility in women, as well as health and vitality in men. Just why it has such an effect on us is perhaps because it is something that is both intimately part of us and yet also something different. Hair is one of the few parts of ourselves we can chop and change and – unlike most of the rest of the human body – it can grow back and rejuvenate: a quality integral to the story of Samson. While we feel no physical pain when we cut our hair, though, our emotional and psychological bonds are often more deeply rooted. A malleable, yet elemental, assertion of self, it acts as a bridge between the psyche or body and the costumes and fashions we use to adorn ourselves.

As we move further forwards into an age in which science and technology are increasingly part of our everyday reality, our attachment to the essential, life-affirming quality of hair remains undiminished. Working at the forefront of contemporary hair science, an understanding of the links between hair and personal identity lies at the heart of Meshkati’s approach to the corresponding effects of hair loss. Aware that hair is no mere external appendage, or simple covering, Meshkati’s clinicians use groundbreaking techniques to help re-connect clients with one of the most treasured conduits of personal confidence and self-expression. Blending an appreciation for the beauty of hair with meticulously researched procedures, Meshkati brings an artistry to hair restoration, guided by the rich history of hair and its central place in our shared visual culture.